LIFE AT BUTLERS - 04

The war

By Martin Edgar

4. THE WAR

When war broke out in 1939, the usual things happened. The windows were criss-crossed with brown paper tape, to stop glass flying around too much if the windows were blown in. The air raid shelter was dug out by the kitchen path, all the windows were covered by blackout material so that not a chink of light showed at night, and of course we each had our gas masks, to be carried at all times (a rule honoured more in the breach than in the observance). A few years earlier, tall lattice masts had been built at Canewdon, the early radar which proved so invaluable. You could see them from the attics at Butlers, looking north across the Creek to these half dozen oversize electricity pylons five miles away. The Army also requisitioned a field on the corner opposite Slated Row. Wooden huts went up, and gun emplacements were made for a battery of 3.7" anti-aircraft guns, with searchlights as well, and we called that the "Camp". Rochford airport was turned into a fighter aerodrome.

As we were near the mouth of the Thames, we could expect enemy bombers to pass overhead on their way to London, and you soon learned to tell them apart. Our planes had a steady note to the engines, but the enemy ones had a kind of throb. We also got used to the sound of the guns going off only two fields away, particularly at night, as we slept in the drawing room downstairs when the raids were at their peak. That was our main concession to events. It was even exciting to watch, with the searchlights sweeping the sky, and occasionally lighting up a bomber or pursuing fighters, and sometimes a solitary airman swinging on his parachute.

I was sent down to Hampshire for a couple of months during the height of the Battle of Britain, and stayed first with Uncle George and Aunty Margaret Joan at Manor Farm at West Worldham, then with the Baigents at East Worldham, and finally at Old Place where Aunty Ethel was living with Uncle Harold and his wife Sybil, and the dour and rather silent Grannie Edgar in her black bombazine. Aunty Ethel was good fun and we became friends, going for walks and collecting snails from under the wall while she gardened.

Life then settled down, and we got used to the rationing. We each had a ration book with coupons for meat, butter, etc. When you went to Shelleys the grocers or Fance the butchers in Rochford Square, the coupon for the week would be cut out and taken for the goods purchased. At one stage we decided to keep a pig, and had to surrender our meat ration in return. That pig produced the finest sausages I had ever tasted.

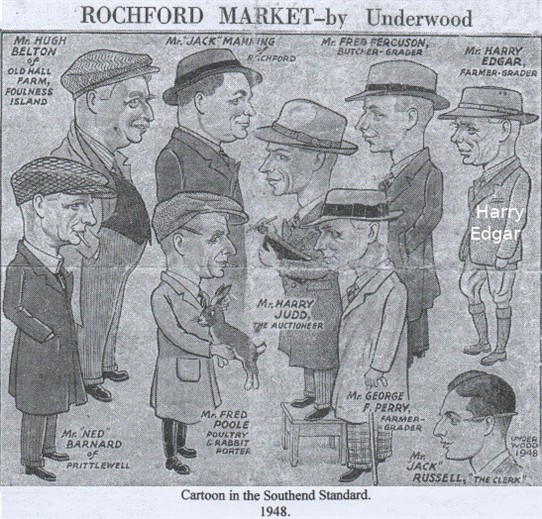

Rochford market still continued. Father was the official sheep grader, and would dress up to go to market, with breeches, well polished full length leather gaiters, jacket and tie. He made a dapper figure with his slight frame. He sometimes used to count his sheep in Cumbrian: yan, tyan, tethera, methera, pimp, sethera, lethera, hovera, dovera, dick. One to ten, if you haven't guessed. 15 was bumfit. I vaguely remember Father as a gentle and perhaps shy man as was Mother, though she projected a more stern exterior, and they both had high principles. It was a bit later that I discovered that Mother had a nice giggle when relaxed and comfortable in herself. Father was Churchwarden at Sutton church, and Mother followed him later in that role.

In 1941 I went to a kindergarten in Rochford in the mornings. It was in the back lane running behind the Square down to Warrens Garage. Mother would take me in first thing, and I would be collected by the milk float and brought home by the milkman for lunch. I clearly remember clip-clopping home in the summer sun, past the elm trees by the roadside and with one or two yellow-hammers singing in the hedgerow, since I was put to bed with sunstroke that afternoon.

We had a milk round in Rochford at that time - a pony and milk float carrying churns of milk and a pint measure. So customers had to provide their own containers, and the milk would be ladled into them by the pint. It was good creamy milk from our Shorthorn herd. Fance also delivered occasionally to us. They had a high-wheeled dogcart, smartly painted in cream and green, with a high stepping hackney pony in the shafts. It made a fine sight as it swept down the drive at a fast trot, and round in front of the house. Their butcher's shop in Rochford was very much in the old style, with the two Fance brothers doing the serving, and the rather fierce Miss Fance at the back in her cashier's cubicle - so that those handling meat did not handle money. Shelleys' on the corner of the Square was also the traditional grocers, with tiers of containers up the wall behind the counter. Individual requirements would be weighed out and put in brown paper bags, or if a small quantity put in a paper screw.

Then in 1942 I was six and went off to Alleyn Court School. Bill and Robert had already gone there. Alleyn Court had been a Westcliff school, but was evacuated down to Devon for the war. It had taken Bigadon House, a four square stone Georgian country house, some two miles outside Buckfastleigh. We would be taken up to Paddington station to join the school train, each carrying a small attaché case. Our clothes had already been packed into the big trunks and sent off by rail by Passenger Luggage in Advance a few days earlier. Mother would say goodbye and we boys would go to our allotted compartments - shades of the Hogwarts Express! Then there was the long journey down, but it got more interesting after we passed Exeter and travelled by the sea with its Brixham trawlers and other boats. We got off at Newton Abbott and boarded coaches (we were about 60 strong) to Bigadon, entering by the main gates and down the drive through laurel and rhododendron woods to the house, which stood on a high bluff some 200 feet above the main road below.

The house had no electricity, but it did have good central heating fired by coal and stoked by Walton the caretaker. So it was Aladdin lamps, oil lamps and candles. Chad (the Matron) was a small, fierce and energetic person, who went so fast down the corridors that the flame on her candle went down to just a red glow. We always wished for it to go out, but it never did. I visited Chad many years later, and found that she was actually a real softy. It was only when the chatter from the dormitory got to high decibel level that she would call out mock severely, "Stop talking, you boys." Rationing meant we had a tin of jam to last us the term, and we all manoeuvred to avoid the red jam. The marmalade was much better. Dried egg made up was a curiosity to be endured, but what we really enjoyed was the bread and dripping that Mrs Walton, the cook, brought out at elevenses. There was plenty of that, as it was off rations. There was always plenty to do, the staff were good and we enjoyed ourselves. So it was no great hardship to be away from home for most of the year, coming home for four weeks at Christmas and Easter, and eight weeks at harvest time.

Back home life continued on a pretty even keel. We were not much troubled by the actual war, at least as far as I remember, though William Cadge (always "Cadge" to us) lost two sons, both shot down in the Air Force. Hodgie had left to join up, and I did miss her for a while. Otherwise, life trundled on with the effects of wartime becoming normality.

At one stage the army put a solitary Bofors gun in Big Field, intending to catch any enemy bombers flying low up the Creek to get under the radar, but nothing came of it. One Heinkel bomber was brought down in Big Field, and was a ready source of the odd metal bits that small boys like to collect. If an incoming enemy bomber was really caught, it would drop its load of bombs and run for home. So we used to find the occasional unexploded incendiary bomb on the Marsh, and carry it home, swinging the 18" bomb from its fins. These were put in a shed, and the Bomb Disposal Officer used to drive over to collect them.

In 1942 the Twins were born. I remember Mother going off to a nursing home at Danbury for this birth, and it was novel to have these new bundles around. Then Miles was born in 1944, again I think at Danbury. It was not surprising that Mother should go away for the births. She was after all aged 44 by then, and had only had her first child at 31. She said that by the time you got to your sixth child, it was easy to cope - you just hung it on the line to dry...